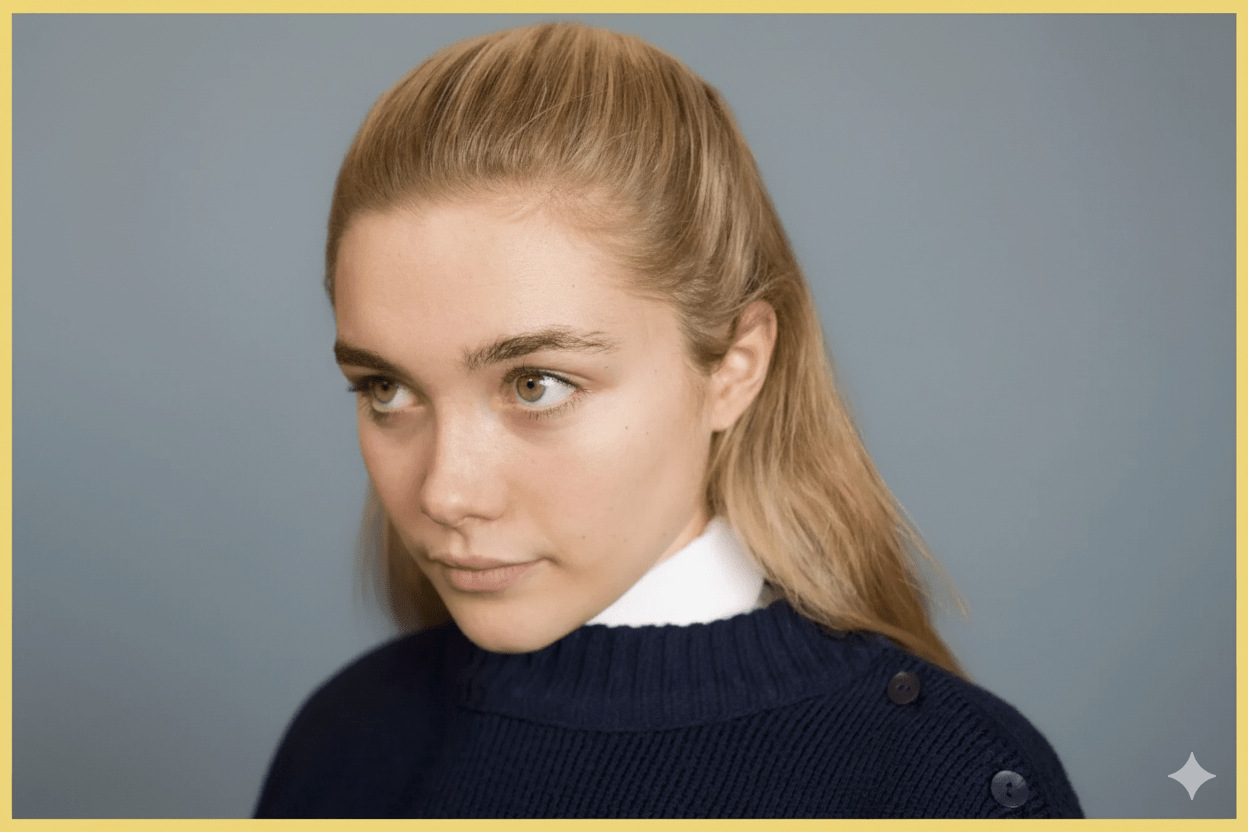

There’s a reason the “I’m not a poet, I’m just a woman” moment has lived rent-free in my head since 2019. In Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, Florence Pugh’s Amy March delivers a cool, lucid monologue on why marriage, for her, is an economic decision.

It’s the scene where Amy tells Laurie, with calm precision, why marriage for her is not only about love but about survival, and in doing so, she lays out the stark truth: women in the 19th century had no money of their own, no property rights, and no legal independence.

This speech has been called one of the defining feminist moments in Gerwig’s film. But what makes the Amy March speech so powerful is not only what she says – it’s how she says it, and how Florence Pugh delivers it.

Gerwig’s Adaptation of Little Women

Greta Gerwig’s Little Women is a retelling of Louisa May Alcott’s 1869 novel. But in Greta Gerwig’s re-telling, she did what she does best – portraying women in a way that feels layered rather than straightforward.

She shows us the clash between girlhood dreams and the compromises of adulthood, and in doing so, she gives us a version that speaks straight to today’s women and audience.

The Context Behind the Scene: The Little Women Monologue

Louisa May Alcott’s original Little Women did not include this exact monologue. It was Gerwig who added it after conversations with Meryl Streep, who plays Aunt March in the film. Streep reminded Gerwig that women in the 1860s had very few rights: their property, wages, and even children belonged legally to their husbands. Gerwig decided this context needed to be spoken aloud in the film, and she gave those words to Amy.

This choice is crucial. It transforms Amy from the shallow, spoiled sister many readers remembered into a character of clarity and realism. She is no longer just “the girl who burned Jo’s manuscript.” She is someone who sees the system for what it is and chooses to navigate it with strategy rather than delusion.

Pugh’s Performance: An Acting Analysis

Florence Pugh delivers the monologue with remarkable forethought. She makes her point without pleading. Instead, her tone is measured and matter-of-fact, which makes the truth even harder to ignore.

Here’s Amy’s speech in full:

“Well. I’m not a poet, I’m just a woman. And as a woman, I have no way to make money, ot enough to earn a living or to support my family. And if I had my own money, which I don’t, it would belong to my husband the minute we were married. If we had children, they would be his, not mine. They would be his property. So don’t sit there and tell me that marriage isn’t an economic proposition, because it is. It may not be for you, but it most certainly is for me.”

Amy sits with Laurie in a sunlit Paris room, and she spells out the logic: marriage is the only way a woman of her time can secure her future.

The staging of the scene adds weight to her words. At times, Amy stands while Laurie stays seated, shifting the balance of power. The camera lingers on Pugh’s face, catching the small details like her steady gaze, the quick flicker of doubt, the slight tightening of her jaw. By the time the scene ends, it’s no longer just Laurie who sees Amy differently—it’s us, viewers, too.

Why the Monologue Matters

For decades, she was often the least liked March sister, dismissed as selfish or petty. But Gerwig’s version, and Pugh’s performance, show that Amy is not petty at all. She is pragmatic. She knows the rules of the world she lives in, and she refuses to pretend otherwise.

Feminist critics have celebrated this change. By spelling out the legal and social limits of women’s lives, the film shifts the blame away from individual women and toward the system itself. Amy’s decision to “marry well” is no longer shallow, as it is survival, just as it is for many women in the real world.

Gerwig’s Vision

The monologue also reflects Greta Gerwig’s larger themes as a director. Across her films, she returns again and again to women, art, and money. Jo negotiates the price of her book; Meg struggles with the cost of domestic life; Amy delivers this economic manifesto. Together, these threads highlight how making art and making a life are tied up with making a living.

Gerwig’s structure of storytelling and the way she cross-cuts between childhood and adulthood make Amy’s speech even more impactful. We have just seen Meg’s financial struggles and Jo’s passion for independence. By the time Amy speaks, we understand that her perspective is not a cold take but rather a necessity.

Feminist Resonance Today

Watching Amy calmly explain that marriage is “an economic proposition” hits differently in 2019 when it was released than it might have in 1869, but the resonance is sharp. It reminds us that women’s choices are never made in a vacuum. Social and financial systems still shape what is possible. Many viewers, especially women, recognized themselves in Amy – it may not be in her exact circumstances, but in the balancing act of love, ambition, and financial reality.

This is why the speech went viral online after the film’s release. It was clipped, shared, and quoted as a piece of timeless feminist reasoning. Suddenly, Amy March was no longer the villain of the story.

Lasting Impact

In the end, Florence Pugh’s monologue is not just a highlight of Little Women. It is a statement about how women’s lives have always been shaped by structures larger than love or personality. It turns Amy March into a feminist icon of realism, and it shows Gerwig’s genius for marrying classic literature with contemporary urgency.

When I think of Little Women, I don’t think first of who Jo marries, or of the warmth of the March household. I think of Amy, in Paris, calmly telling Laurie that she cannot afford to be a poet. That moment has become a classic scene, both heartbreaking and liberating.

It is cinema as truth-telling, and it is why Greta Gerwig’s adaptation feels both timeless and fiercely of our moment.