Marco Bellocchio

Birthdate: Nov 9, 1939

Birthplace: Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Marco Bellocchio is one of the most consistent and most adventurous of today's Italian directors-an achievement all the more remarkable given that he made his feature debut almost fifty years ago. Over those years, he has amassed a body of films that encompasses a large number of original screenplays, adaptations of the likes of Pirandello and Kleist and personal, quasi-autobiographical work. What unifies these films is the beauty and originality of Bellocchio's images and his unceasing quest to understand the place of the individual in contemporary Italy and contemporary cinema. After making a few shorts, Bellocchio announced himself with his ferocious first feature, the acclaimed Fists in the Pocket (1965). This caustic and anarchic look at an extremely troubled family launched him instantly to the first ranks of the Italian film scene, alongside Antonioni, Pasolini and Bertolucci. For the next several years, films such as China Is Near (1967) and In the Name of the Father (1971) found Bellocchio examining the turbulent world of leftist politics and revolutionary dreams with an eye both sympathetic and jaundiced. During the 1980s and 1990s, under the spell of unorthodox-and, to some, controversial-psychoanalyst Massimo Fagioli, Bellocchio's emphasis turned to examining the interweaving of family dynamics and sexual desire as they produce and undermine personal identities. Films such as A Leap in the Dark (1980) and Devil in the Flesh (1986) create complex allegories of an audacious originality. More recently, Bellocchio has turned to more straightforward narratives in a number of films that examine Italy's recent past and its present, from The Nanny (1999) to one of his most recent works, Dormant Beauty (2012). Shifting brilliantly from realist fiction to archival footage to the imagery of dream or fantasy, all within a single film, this recent period has returned Bellocchio to the forefront of contemporary cinema, while combining the lessons learned from both the previous political and allegorical work. What has remained constant is Bellocchio's searching critique of the institutions that control individuals and organize the flow of power: the army, political parties, schools, the state and its laws, the Church, and the family.

Known For

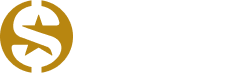

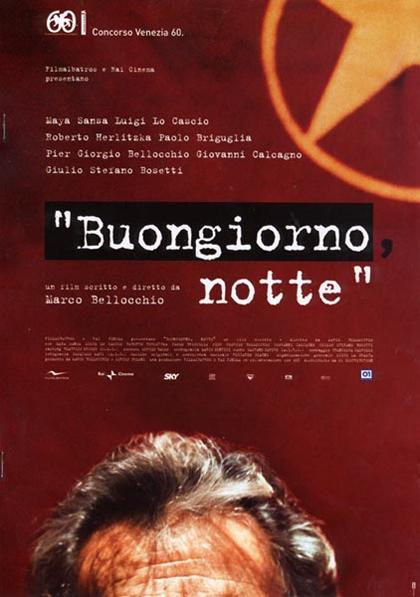

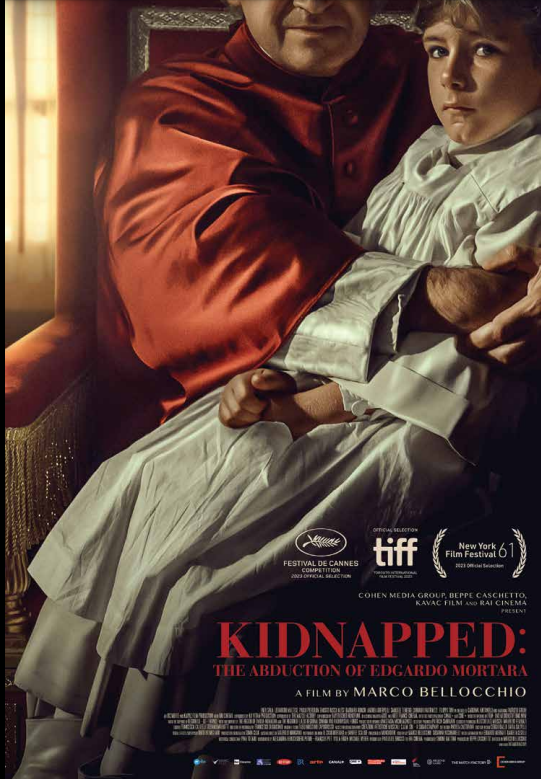

Marco Bellocchio Movies

actor

Previous (61)

director

Previous (3)

self

Previous (1)

People Also Searched For